#30TubeReads: The End of Loneliness by Benedict Wells

One Day but make it European, darker and more circuitous!

WARNING: This one is chock-a-block with spoilers.

I have a love/hate relationship with the will they/won’t they trope. Books, movies and shows that follow this pattern of romantic storytelling are equally intriguing and frustrating. Friends managed to keep me hooked on the will they/won’t they journey of Ross and Rachel for 10 seasons. Occasionally, you’ll still find me yelling at Jennifer Aniston and David Schwimmer to kiss already! I religiously reread the OG will they/won’t they classic, Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë, every couple of years. (It is not my all-time favourite classic, but it is pretty up there.) Reader, I am exasperated (every single time). And then there’s my favourite romantic drama that I love to hate, yet, have hate watched more times than was probably good for my sanity: One Day.

One Day is a 2011 romantic drama starring Anne Hathaway and Jim Sturgess. Apart from having an unbelievably good-looking cast, the movie has a storyline that spans across two decades. It follows the two protagonists Dexter Mayhew and Emma Morley on the same day, every year: July 15, as they go through the different highs and lows of life. They meet on their graduation day in 1988, and despite the insane chemistry between them they decide to be ‘just friends’. Cut to: twenty years of being each other’s closest friends, confidantes, going skinny dipping, being jealous of each other’s relationships, failed marriages, failed careers, failed stints in rehab, and a rather long list of things that can happen to two people. All along there is the underlying sub context of Dex and Emma being perfect for each other. Everyone can see it… BUT THEM!

Now it is spoiler time. (Although, with the data that I have already presented to you you already know where the first half of the spoiler is going.) After 20 years of denying their feelings for each other they decide to give a relationship a shot. And guess what, they are perfect for each other. They are happy and at peace. They own a cute cafe together and they live happily ever after. (Now this is the bigger SPOILER. So skip it if you want to. But mind you the rest of this blog won’t make much sense if you do. And the movie did release in 2011, so if you haven’t seen it yet maybe you’re never going to.) Then the last 15 minutes of the movie happens. Emma dies in quite a brutal, jump scary, absolutely devastating, and arguably infuriating road accident, while she is cycling back home to Dex.

Let it sink in.

2 hours of a movie - a romantic movie at that - for that end.

A will they/won’t they build up for fate to say ‘Oh, they won’t.’ just when you think that they will.

Now, take that same feeling of being robbed of a satisfying ending and imagine it came after you spent about a day and a half reading a 300-page novel. The feeling is so unsatisfactory that even the beautiful writing, the brilliant translation, and the interesting discussions about what it means to be a writer, do not make up for it.

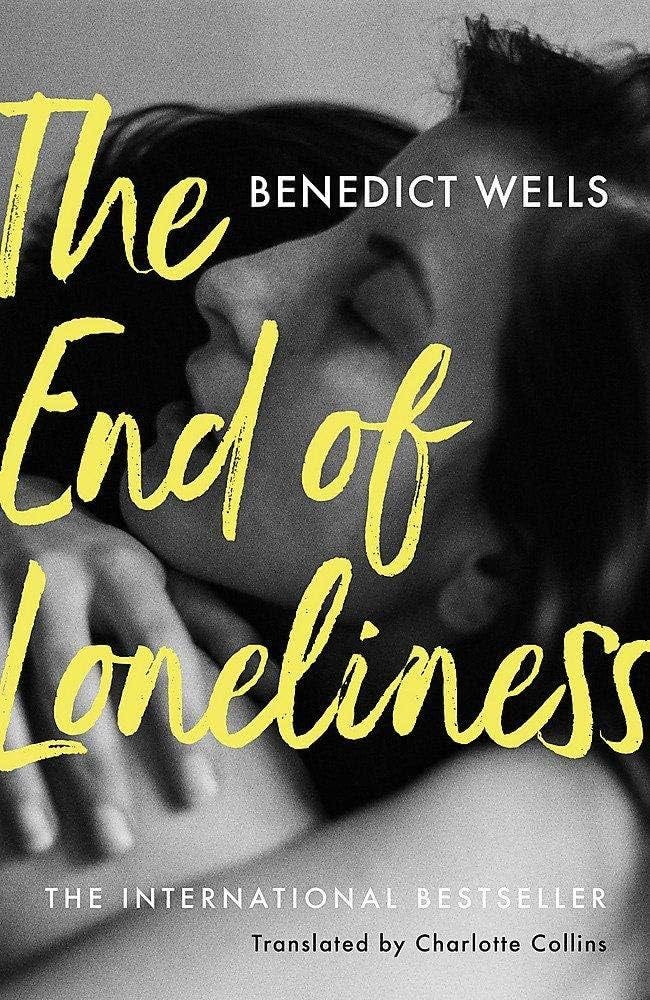

I read Benedict Wells’ The End of Loneliness (translated by Charlotte Collins) as part of the #30TubeReads challenge after I spotted the striking cover on the Northern line. I feel compelled to mention that the woman reading it was possibly one of the most aesthetically dressed people I have seen in my life. The number of times I have googled tan overcoats in the last couple of weeks is slightly embarrassing.

The first half of the novel feels like a different book from its second half. His writing does not lose its charm, and nor does the pacing of the plot change. It is just because while the first half of the book is a delicate study of grief, childhood trauma, and sibling relationships, the second half is a circuitous One Day-esque tale, just more European. The fact that you can continue to see the signs of the same discussions as the first part but undeservedly neglected just makes the experience of reading the book a little annoying.

The novel follows three siblings: Liz, Marty, and our main character, Jules, as their childhood abruptly ends and the trajectory of their lives change forever, after the sudden death of their parents. They are sent to boarding school and are forced to live apart, finding their own ways to deal with the grief of losing their family in the blink of an eye. Each sibling finds a different way of doing this, for Jules it is retreating inward and rejecting everything that made him feel closer to his parents. He also finds some form of comfort in his friend Alva, who is the only one to stand up for him when he’s being bullied as the new kid. And so starts the will they/won’t they tale.

Wells does a good job of describing the ways in which the methods of coping with grief set the siblings apart. He slowly reveals different things about the days leading upto the accident that took the lives of the parents so that the reader can piece together and make sense of the psychological states of the siblings along with them. It is not possible for us to ever know our parents as individuals, our relationship to them will forever bias our opinions about them and their decisions. Even as adults we look at our parents from the viewpoint of children, and that is even more true for the three siblings of this book as they never get to know their parents beyond childhood. Wells’ descriptions of the lives of the siblings, their rebellions and their victories, seems real. There is an authenticity in his writing that does not feel like he is emotionally manipulating the reader in any way. (I am looking at you, A Little Life by Hanya Yangihara.)

These are themes that underline the entire novel even when the second half becomes a more introspective look into Jules’ character. As a character Jules is very similar to Dexter from One Day. He is lost. He does not know what he wants to do with his life. But while Emma becomes the stable and reliable point in Dexter’s life, the death of his parents and the disappearance of Alva, leaves Jules without any anchor. He drifts from career to career, losing money, breaking ties, and struggling to stay afloat. Even when he finds stability, unsatisfactory and undesirable, he abandons it the minute he realises that there is a chance of reconciliation with Alva. The fact that she is married to the author they both idealised (This point of the story leads to a brilliant description of what it means to be a writer losing his identity as his loses words and narratives.) and not available to fulfil his teenage romantic dreams does not matter. His decision pays off, but that’s besides the point.

Every part of Jules and Alva’s relationship initially is simultaneously a disaster and inevitable. Both of them make morally questionable decisions without any regrets or concerns about the consequences of their actions. But Wells handles even this aspect of the novel with grace. There is no judgement and the facts are presented to the reader in a way that’s meant to say ‘such things happen’. This was not my problem with the book. It is actually one of the things I enjoyed about Wells’ writing. What rubbed me the wrong way was the exploration, or lack thereof, of Alva’s character.

While the other characters are fully-fleshed out, Alva is not given the same attention. In the first half of the book as Jules develops an infatuation for his classmate and friend, this ambiguity is intentional. And it meets its goal. But as the story progresses and Jules and Alva finally get together (Spoiler: they will, after all!) even when snippets of Alva’s backstory become evident to Jules, and through him the reader, they are disjointed. The puzzle pieces don’t fit together to form a full picture of her character. Alva is a blurred figure, and the reader is meant to fall in love with this hazy depiction of the character, along with Jules. In my opinion, the books falls short in this aspect.

There is a similarity between the cult classic 500 Days of Summer and the Bollywood film Meri Pyaari Bindu that goes beyond unfulfilled love stories. In both movies the male main characters, and narrators, don’t fall in love with the main love interests so much as fall in love with the idea of them. They form an ideal of these women in their heads, that has very little to do with the women themselves, and then are infatuated with those ideals. It is not surprising when their relationship with the real women then fall apart. Something similar seems to be happening in The End of Loneliness, however, Jules is never criticised for that. Wells does not seem to be intentionally saying that Jules falls in love with idea of Alva but to the reader that’s what it feels like. Just like calling Summer and Bindu ‘Manic Pixie Dream Girls’ is an injustice, labelling Alva that way is also unfair. However, her character and the reasons behind Jules’ feelings are gaps in an otherwise polished story.

Another spoiler: The other thing that reminded me of One Day while I was reading this novel was the end. Jules and Alva get together (decades after they first had the opportunity), have twins (a girl and a boy, the perfect combination), and dream of growing old together. But once again fate says ‘Oh, they won’t’ and Alva is diagnosed with cancer. The book is an ultimate example of setting up delayed gratification and then taking it away at the last minute. You want them to have the happy ending, you want Jules to keep the one good thing that has happened to him after all the tragic incidents of his life. But Wells, the decider of the fate of the characters, decrees that it is not to be.

As a reader it is frustrating. In the same way that I have the urge of just not watching the end of One Day. (I wish I could be Phoebe and just not know the sad endings of movies.)

But these narratives are real because they seem to say that things are not always going to go the way you want them to. The moments of happiness and peace (Jules and Alva’s domestic bliss) are not less special because they can be taken away before they know it. The message of The End of Loneliness, right from the first anecdote of the siblings watching another family’s picturesque picnic getting tragically interrupted when the family dog falls off a cliff, is that the good things can vanish forever in the blink of an eye. All the things one takes for granted or believes are permanent are actually unreliable. However, the true strength of a person is evident only when we see how they deal with that loss.

Now I cannot say whether I agree or disagree with Wells’ decision to give us this real ending. Books, for many including me, are escapism from such realities of life. Yet, art is a reflection of the real world and if I can appreciate his exploration of grief and loss, I can appreciate the end of the book, too. However, I cannot promise that I won’t skip the last few chapters of the book if I ever reread it.

This is a genre of book that I really enjoying immersing myself in. Some books with explorations of sibling relationships that I have enjoyed are When God was a Rabbit by Sarah Winman, Mai by Geetanjali Shree, The Dutch House by Ann Patchett, The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy, Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng, and Malibu Rising by Taylor Jenkins Reid. This book was a unique take on the romantic drama genre and if that’s your cup of tea then a few that I recommend are: Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan, Ghosts by Dolly Alderton, Early Morning Riser by Katherine Heiny, and (this one I’m recommending a little grudingly) Normal People by Sally Rooney.

With that another review for the #30TubeReads challenge comes to an end. The End of Loneliness is a short book that managed to make me feel thoroughly engrossed in the tale. Other than giving me a reason to read the book, I’m grateful for the woman on the Northern line for showing me just how to style a tan overcoat like a true aesthetic Londoner.